INTRODUCTION

Severe maternal morbidity (SMM) affects more than 50,000 patients per year or approximately 2% of all deliveries in the United States, with steadily increasing frequency (“Severe Maternal Morbidity in the United States,” n.d.). The etiology for this increase is unknown, but may be secondary to changes in the overall health of the population (“Severe Maternal Morbidity in the United States,” n.d.; Hinkle, Sharma, and Kim 2012; Fisher et al. 2013; Campbell et al. 2013; Small et al. 2012). We previously demonstrated that premature delivery, and in particular, periviable birth (defined as delivery between 20 0/7 through 25 6/7 weeks of gestation) (Hinkle, Sharma, and Kim 2012), is associated with high rates of maternal morbidity (17.2%: periviable births, 5.1%: preterm births, and 2.7%: term births) (Rossi and DeFranco 2018).

This high rate of maternal morbidity is likely due to a combination of underlying maternal medical co-morbidities, obstetric complications, and obstetric interventions that are associated with periviable birth (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2017). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine acknowledge in the Obstetric Care Consensus, “Periviable Birth,” that while some obstetric interventions aimed at optimizing neonatal outcomes pose little risk to the patient, others, including classical cesarean delivery, may result in significant short-term and long-term maternal morbidity for uncertain neonatal benefit (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2017). Despite this cautionary guideline, periviable cesarean rates have increased over time (Stoll, Hansen, Bell, et al. 2010; Costeloe et al. 2012; Ancel, Goffinet, and EPIPAGE 2 Writing Group 2014; Rossi, Hall, and DeFranco 2019).

There is a paucity of research on the prevalence and type of SMM in the periviable period, particularly the association between cesarean utilization and SMM. In this study, we sought to characterize the rate and type of SMM among patients who delivered in the periviable period and the association between cesarean and these adverse maternal outcomes.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

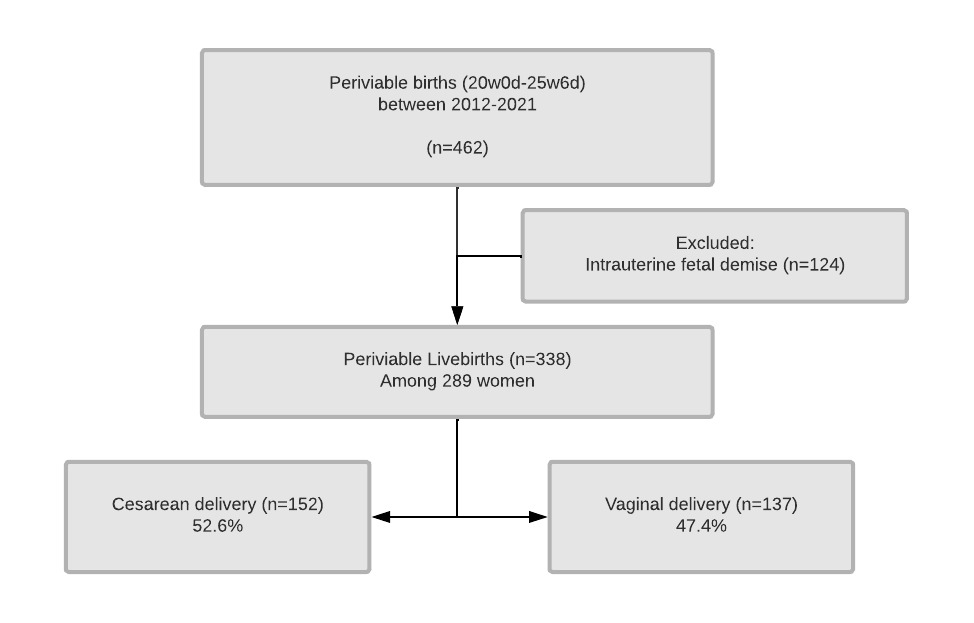

We performed a single-center retrospective cohort study of all periviable births occurring at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center from 2012 to 2021. The protocol for this study was approved by the Human Subjects Institutional Board Review at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center. Periviable birth was defined as livebirth occurring between 20 0/7 - 25 6/7 weeks of gestation. Pregnancies that resulted in fetal demise were excluded, consistent with prior literature (Reddy et al. 2015; Romagano et al. 2020). Data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at University of Cincinnati (Harris et al. 2009).

Our primary objective was to determine SMM rate among patients who delivered in the periviable period. SMM was defined using the Gold Standard Severe Maternal Morbidity guidelines established by Main et (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2016) and published in the Obstetric Care Consensus No.5 “Severe Maternal Morbidity: Screening and Review.” (Main et al. 2016) This list of 37 maternal morbidity indicators is organized into the following SMM categories: hemorrhage, hypertension/neurologic, renal, sepsis, pulmonary, cardiac, intensive care unit/invasive monitoring, surgical, bladder, and bowel complications, and anesthesia complications (Box S1). In cases of multifetal births, the number of SMM was counted once per mother.

The secondary objective was to compare the rate and risk of composite SMM between vaginal and cesarean delivery groups to determine the association between periviable cesarean utilization and SMM. Differences in maternal demographic, social, medical, obstetric, and delivery characteristics were compared between patients who underwent cesarean and vaginal birth. These differences were compared using t-test and chi square analysis, for continuous and categorical data, respectively. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare counts ≤5. Mann-Whitney U test was applied for nonparametric testing. Variables with significant differences in bivariate analyses were selected to perform a multivariate logistic regression for estimation of the adjusted odds (aOR) of composite SMM in cesarean verses vaginal delivery. This regression model was constructed using a backward selection process. As outcome events were rare and there were significant demographic and obstetrical differences between mode of delivery in pretest bivariate comparisons, the number of variables selected was limited to 10 events per variable according to Peduzzi et al to avoid overfitting the model (Peduzzi et al. 1995, 1996). Variables selected for the adjusted model included maternal race, pregnancy induced hypertensive disease, chronic hypertension, delivery indication, pregestational diabetes, and gestational age at delivery.

We then stratified the patients by delivery indication and performed a subgroup analysis. Groups included 1) maternal-indicated (delivery due to maternal illness, pregnancy induced hypertensive disease, or other maternal condition negatively impacted by pregnancy), 2) fetal-indicated (delivery due to fetal distress, non-reassuring fetal testing, cord prolapse, spontaneous preterm labor, or other fetal indication), or 3) dual-indicated (delivery due to both maternal and fetal condition including antepartum hemorrhage secondary to abruption, placenta previa or accreta, or chorioamnionitis). Multivariate logistic regression was performed for each indication group to estimate the aOR of cesarean delivery and composite SMM. Lastly a qualitative analysis, in which the maternal delivery and neonatal record were reviewed for all patients who had an SMM. This was performed by the 3 abstractors (MJ, AB, and RR) to assign likelihood of cesarean causing SMM (causative, likely, possibly, not causative) and likelihood of cesarean mitigating SMM (yes, possibly, no) for each case among patients categorized as “fetal” or “maternal” indicated delivery. These assignments are shown in Table S1 and S2.

Significant differences were defined as comparisons with probability value of <0.05 and 95 percent confidence interval not inclusive of the null value of 1.0. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA Release 15 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Of 462 periviable deliveries during the study period, 124 were fetal demises, leaving 338 livebirths among 289 patients. 52.6% (n=152) underwent cesarean delivery (Figure 1). Individuals for both modes of delivery were similar in age, race/ethnicity, parity, body mass index (kg/m2), substance/tobacco use, and socioeconomical status (Table 1). The individuals delivered via cesarean section had higher rates of medical co-morbidities including hypertensive disease both chronic and pregnancy-induced, pregestational diabetes, and admissions for fetal growth restriction or hypertensive complications. The individuals who underwent a cesarean section were hospitalized longer (9.7±7.2 vs 5.7±5.0 days, p<0.001) and had longer latency from admission until delivery if admitted for preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) (14.4±9.1 vs 6.7±10.5 days, p=0.032) (Table 2).

Patients who underwent cesarean section were more likely to receive other obstetric interventions such as antenatal steroids and magnesium for fetal neuroprotection. Cesarean deliveries also had a longer latency between admission and delivery resulting in deliveries at later gestational ages. Individuals delivered via cesarean section were more likely to deliver due to fetal distress (30.9 vs 2.2%, p<0.001) and hypertensive disease of pregnancy (15.8 vs 2.2%, p<0.001) compared to vaginal deliveries. There was a higher incidence of fetal malpresentation in the individuals who delivered via cesarean section (Table 3).

Among the 289 patients, 19.0% (n=55) experienced ≥1 SMM event. Because some patients had multiple events, the composite rate of SMM events was 52.2 per 100 patients (n=151 events). The most observed SMM categories were hypertensive/neurologic (11.1%), ICU-related (5.5%), hemorrhage (4.8%), and pulmonary (4.2%) morbidities. Composite SMM rate was significantly higher in cesarean deliveries for both the number of patients who experienced ≥1 event (30.9 vs 5.8%, p<0.001) and the number of events per 100 patients (83.6 vs 17.5, p<0.001). By category, the cesarean deliveries had higher rates of hypertensive/neurologic (20.4 vs 0.7%, p<0.001) and ICU/invasive monitoring (9.2 vs 1.5%, p=0.004). Patients who delivered via cesarean had higher rates of continuous infusion of anti-hypertensive agents (15.1 vs 0.7%, p<0.001), administration of IV anti-hypertensives for >48 hours after delivery (13.8 vs 0%, p<0.001), and HELLP syndrome or disseminated intravascular coagulation (6.6 vs 0%, p=0.002). Cesarean deliveries had lower rates of retained placenta (0.7 vs 14.7%, p<0.001) and subsequent D&C (0 vs 10.9%, p<0.001) but higher rates of postpartum endometritis (7.3 vs 1.5%, p=0.022). In the multivariable logistic regression model, cesarean delivery during the periviable period was associated with an increased risk of composite SMM (adjusted RR 6.6, 95% CI 2.2-19.9) as shown in Table 3.

When categorized by delivery indication, 11.1% (n=32) of patients were delivered for maternal indications, 74.7% (n=216) for fetal indications, and 14.2% (n=41) for dual indications. In all three subgroups, SMM rate was higher in cesarean delivery compared to vaginal (maternal: 92.6 vs 20.0%, p<0.002; fetal: 14.4 vs 5.4%, p=0.025; dual: 33.3 vs 5.0%, p=0.045). The association between cesarean and SMM was highest among patients who delivered for maternal indications (unadjusted OR 50.0, CI 3.6-668.3) compared to fetal (unadjusted OR 3.0, CI 1.1-8.0) and dual indications (unadjusted OR 9.5, CI 1.0-86.3). However, these results should be interpreted with caution due to imprecise estimates.

A qualitative analysis was performed by the 3 abstractors (MJ, AB, and RR) of each patient who experienced SMM and their hospitalization to assign the likelihood of causality (causative, likely, possibly, not causative) between SMM and the mode of delivery. Among 15 patients who delivered for fetal indications and experienced SMM, 7 were deemed either causative, likely, or possibly causative (Table S1). Of these 15, 40% (n=6) had ≥1 SMM event. Four of these patients experienced SMM events that can be definitively tied to their cesarean section (prolonged postoperative ileus, bladder injury, small bowel injury). Only 1 had a permanent morbidity, unplanned hysterectomy in an otherwise healthy patient. In 8 patients, cesarean was determined to have either mitigated or possibly mitigated the SMM event. Comparatively, among patients who delivered for maternal indications (n=25), there were no cases where the cesarean delivery was deemed possibly causative. In all 25 of these patients, the cesarean delivery was determined to have possibly mitigated the SMM event (Table S2).

DISCUSSION

Main Findings

We found that nearly one in five patients who deliver in the periviable period experience an SMM event. When stratified based on mode of delivery, the cesarean deliveries experienced significantly higher rates of SMM compared to the vaginal deliveries (30.9 vs 5.8%, aOR 3.9, 95% CI 1.1-14.3, p<0.001). In subgroup analysis of delivery method separated by delivery indication (maternal vs fetal vs dual), 96.2 % of patients who underwent a cesarean section experienced an SMM. Despite higher rates of SMM among patients who delivered by cesarean, a detailed review of SMM cases among those delivered for fetal and maternal indications revealed cesarean as causative in a minority of cases and perhaps mitigated SMM in many cases.

Interpretation

The decision to offer to an obstetric intervention in the periviable period requires equipoise between associated maternal risks and degree of expected neonatal benefit. These clinical decisions should be taken in context of the newborn’s overall prognosis, which changes substantially with increasing gestational age at delivery. There are no randomized controlled trials comparing modes of delivery in the periviable period, however there are limited retrospective studies including our own with mixed conclusions (Romagano et al. 2020; Harris et al. 2009; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2016; Main et al. 2016; Peduzzi et al. 1995, 1996; Tucker Edmonds et al. 2015; Czarny et al. 2021; Reddy et al. 2012; Lee and Gould 2006; Wylie et al. 2008). As such, the Obstetric Care Consensus titled “Periviable Birth” recommends against routine utilization of cesarean for the indication of periviable birth alone (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2017). Blanc et al performed a meta-analysis and systematic review of SMM risk with cesarean periviable birth and found increased risk of SMM if delivered at < 26 weeks (aOR 1.65, 95% CI 1.52-1.78). Romagano et al performed a retrospective cohort study of maternal morbidity between 23-28 weeks and found composite maternal morbidity of 42% vs 45% in the individuals who delivered vaginally compared to cesarean (aOR 1.00, 95% CI 0.27-3.64) (Romagano et al. 2020). Their higher rate of reported maternal morbidity (Jiang 19.0% vs Romagano (23+0 – 25+6 weeks) 60.5%) is likely due to their inclusion of any blood transfusion, hemorrhage, chorioamnionitis, and prolonged hospital stay in the composite morbidity rate; indicators which are not considered severe morbidity by the gold standard.13,16

As the causal pathway to SMM among patients delivering in the periviable period is highly complex with varying degrees of input from underlying maternal medical co-morbidities (i.e. renal disease, preexisting hypertension), obstetric complications (i.e. preeclampsia), and iatrogenic sources (i.e. surgical complications), it is not possible to assume that cesarean delivery necessarily resulted in an SMM event. We conducted a case-by-case review of the 15 patients who delivered via cesarean for fetal indications and who also experienced ≥1 SMM event. It is unsurprising that, among the 4 patients with SMM events that can be definitively tied to their cesarean, the events all fall under the category of surgical, bladder, or bowel complications. There were 3 patients whose SMM events (postoperative sepsis, ICU admission, pulmonary edema) could potentially be related to cesarean, but the causative relationship was less clear. The majority of SMM events in this subgroup were obstetric complications rather than cesarean morbidity. Events in these patients included difficult to control hypertension requiring multiple doses of IV antihypertensives, HELLP syndrome, uterine rupture, placental abruption, and antepartum pulmonary embolism which were not caused by cesarean section, as they preceded the operation. In patients with hypertensive events, it is possible that cesarean mitigated further SMM by expediting delivery and preventing worsening of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. In the patient with uterine rupture, cesarean was necessary to control maternal hemorrhage and reduce further SMM.

We also conducted a case-by-case review of the 25 patients who delivered via cesarean sections for maternal indications who also experienced ≥1 SMM event. Within these 25 patients, cesarean section was not determined to be causative of SMM but rather may have mitigated SMM after extensive review of maternal records. Based on these results, we cannot establish a consistent causal relationship between use of cesarean section and the increased rate of SMM in the periviable period. In some cases, primarily those with fetal indications for cesarean delivery, it is likely that the SMM experienced was a direct result of surgical intervention. In other cases, use of cesarean section likely mitigated further SMM by expediting delivery in an already ill parturient. Therefore, based on this case-by-case review, the association between cesarean and SMM appears nuanced, complex, and may modify SMM risk both positively and negatively.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include the use of a large contemporary database from a single center that provides only high-level maternal care (level IV) and is one of two centers providing high level neonatal care (level III) within a large geographical region serving both metropolitan and surrounding rural areas. The scope of maternal morbidity evaluated is extensive and incorporated a validated criteria for defining SMM (Main et al. 2016). Additionally, this data provides insight and knowledge for providers on the common types of SMM encountered with periviable delivery and allows more informed counseling for at-risk patients.

Our results are limited by retrospective design and inability to determine causality between mode of delivery and SMM. There are also clinical scenarios in which cesarean may have mitigated SMM, which we are unable to measure reliably. We attempted to address these issues by providing a detailed account of individual SMMs among deliveries and performing secondary analyses stratifying by delivery indication and qualitative assessment of the SMM cause in relation to delivery mode. Additionally, this study was conducted using a cohort of deliveries occurring at a single, tertiary academic center, which may make our findings less generalizable to other populations in different areas. There is also a possibility for potential inaccuracies in reporting of data variables, or complete lack of reporting, which is especially true for emergent deliveries. To limit inaccurate or missing data, all records were abstracted by the same 3 reviewers (MJ, AB, RR) during a period in which one electronic medical reporting system was utilized.

Conclusions

One in five patients who delivered in the periviable period experienced a severe maternal morbidity. Utilization of cesarean among those delivering within the periviable period was associated with higher rate of severe maternal morbidity. The higher rate of SMM was likely attributed to the underlying maternal condition and obstetric complications rather than the mode of delivery and, in many cases, cesarean may have mitigated further SMM. Additionally, more research is needed to examine other obstetric interventions geared at prolonging a pregnancy for fetal benefit at the expense of maternal health, and how these impact neonatal and maternal outcomes.

Acknowledgment and Disclaimer

This study includes data provided by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Vital Statistics System, which should not be considered an endorsement of this study or its conclusions. No funding was obtained in support of this study.

Corresponding Author

Megan Jiang BS, BA.

University of Cincinnati College of Medicine

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Medical Sciences Building, Room 4555

231 Albert Sabin Way

Cincinnati, OH 45267-0526

Office phone: 513-558-8448

Mobile phone: 513-502-2261

Fax: (513) 558-3558

Email address: jiangm5@mail.uc.edu

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Contributions to Authorship

RR conceived of the project. RR, MJ, and AB were involved in experimental design. MJ, AB, and RR abstracted data from manual chart review and created the database. RR performed statistical analysis. RR and MJ interpreted data. MJ wrote the original draft of the manuscript. RR, MJ, ED, and AB edited and revised the manuscript.