Introduction

Perineal laceration repair is one of the most common procedures delivering providers will encounter. Vaginal laceration rates vary based on patient characteristics, birth settings, and obstetrical care practices, but overall, 53-79% of women will sustain some type of laceration at vaginal delivery, mostly first- and second-degree (Smith et al. 2013; Rogers et al. 2014; Vale de Castro Monteiro et al. 2015). Third- and fourth-degree lacerations, also known as obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS), The 1998-2010 US nationwide inpatient sample reported a third-degree laceration rate of 3.3% and a fourth-degree laceration rate of 1.1% for women who had vaginal deliveries (Friedman et al. 2015; Dudding, Vaizey, and Kamm 2008).

While laceration repair experiences typically begin early in residency, the chance to be involved in clinical training of higher degree lacerations is lessening. This data is not directly tracked by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) but can be extrapolated based on clinical trends. While the decreasing rate of operative deliveries and episiotomies has lessened the incidence of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS) (“ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 198: Prevention and Management of Obstetric Lacerations at Vaginal Delivery” 2018) it has, in effect, decreased the opportunities for learners to gain experience from complex perineal laceration repairs.

Simulations are an important tool in training. They promote critical thinking, and it is a safe way to apply concepts in a stress-free environment. Simulations in obstetrics and gynecology improve team performance and decrease patient morbidity (Wu et al. 2019). Current training models, like the beef tongue and silicone replicas, do have the advantage of a more lifelike tactile sensation. But these models are more costly, can only be used once, and are technically difficult to construct (Illston et al. 2017). Thus, our team set out to design a model to simulate perineal laceration repair that is affordable, reproducible, and realistic. We then surveyed our team of residents to determine the validity, applicability, and the educational impact of the model.

Materials

-

For Model:

-

1-inch diameter pipe-insulator cut into 4-inch segments

-

Rubber utility gloves

-

Caulk saver cut into 4-inch segments

-

Wooden board for device base (any wooden board sufficient)

-

Wood glue to attach segments

-

1-inch diameter pipe base grounder

-

1-inch diameter pipe elbow

-

5 Flat headed pins (to attach the pieces)

-

Rubber bands and 2 highlighters to stabilizes device

-

Box Cutter and/or scissors (to make the adjustments)

-

-

To aid in suturing

-

Assorted 3-0 and 4-0 Vicryl suture

-

Needle drivers, forceps

-

Allis clamps

-

Suture scissors

-

Methods

The step-by-step instruction with photos describing how to build the low-cost perineal model and the stand can be found in Appendix A. The materials are available at most local hardware stores.

All the residents in our four-year Obstetrics and Gynecology program were surveyed. They were asked to follow the written instructions to build a model and place within the stabilization base. The time it took for them to set up the model was recorded. Of note, the model can also be stabilized on a doorhandle or be handheld. The participants were then asked to perform second degree and fourth degree laceration repairs, respective to their skill level. A facilitator was present to aid in the repair and provide feedback.

Following the workshop, the participants completed a survey. The questions assessed the following: ease of use, learners’ self-assessment of their skills before and after the training, and desire for future use of the foam model. The learners were also asked to compare the ease of use and ease of set up to the beef tongue model, which had been utilized by the learners 3 months earlier. The time it took to set up the beef tongue model was recorded at that time.

Results

Learners and faculty were timed setting up both the beef tongue and the foam perineal laceration models. The average time required to build the foam model was about 5 minutes. The cost of the disposable portion was $2.09 per unit. The beef model took participants an average of 15 minutes to prepare and cost $16.50 each and was discarded after a single use due to risk of spoilage. Our model by contrast could be reused several times before the foam started to break down.

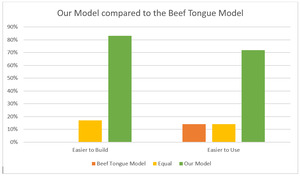

A total of 9 resident providers took part in the beef tongue model simulation and our low-cost simulation. There was an equal distribution of levels of training, one third of participants were PGY-1, one third were PGY-2, and one third were PGY-3 or above. A survey was provided to residents and medical students after using both models, with key results displayed below. All participants found the model to be easy to build and user friendly. There was support for the model to be included in the teaching curriculum. We compared the comfort level of the participants performing second degree repairs and OASIS repairs before and after the simulation, and there was a mild to significant increase in comfort performing these repairs after participating in the simulation (Figure 1). Additionally, compared to the beef model, our model was significantly easier to build and use (Figure 2).

Discussion

Perineal repairs are an important component of the education of delivering providers. While experiences in repairing first- and second- degree lacerations may be plentiful, clinical trends are decreasing the opportunities for clinical experience in repair of third- and fourth- degree lacerations.

Current laceration repair models are expensive, have limited use, and are cumbersome to assemble. We set out to design a low budget model that could be easily recreated, has reusable components, is affordable, and providers a valuable educational experience.

Our model received positive feedback in our institution, with unanimous recommendation to include the learning curriculum. The model is 87% less expensive than the beef tongue, it takes one third of the time to build, and it is reusable. All residents felt they had a positive impact to their confidence in the repair after using our model.

There are some limitations to this study. The beef tongue simulation was completed 3 months before the foam model simulation which could lead to recall bias. Ideally, we would have directly compared both models on the same day, but it was not feasible at the time. While there are some limitations, the positive feedback we have received suggests there is a need for similar models. Our future goal is to design a second perineal simulation that we can bring to a larger audience, with improvements to the design based on feedback and comments from participants.

Overall, our model was seen as a useful training tool to be used in addition to our current curriculum. It does not require significant preparation to build or use and it affordable enough to allow frequent use. We believe our model will have a positive impact in the education of Obstetrics and Gynecology residents, as well as Midwifery students, Family Medicine residents and medical students in our institution. We present it as an additional tool for training programs to utilize in their clinical curriculums.