Introduction

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is defined by The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder, Fifth Edition (DSM-V), as a pattern characterized by tolerance, craving, inability to control use, and continued use of opioids despite adverse consequences (Gynecologists 2017; Krans and Patrick 2016). This disorder affects all races, socioeconomic backgrounds, ethnicities, and geographic regions across the United States (Haycraft 2018). Unfortunately, OUD has increased over the past decade, including an increased use in pregnancy of over 120% from 1998 to 2011 (Krans and Patrick 2016; Haycraft 2018).

The increase in use and misuse can be attributed to the opioids’ mechanisms, which include diminishing the intensity of pain signals through opioid receptors, and causing a feeling of euphoria (Gynecologists 2017; Stanhope, Gill, and Rose 2013). Patients may become physically dependent with regular, long-term use; and manifest with a variety of withdrawal symptoms. Current pharmacotherapy treatment options for OUD rely on medications, like methadone and buprenorphine, that act upon the mu opioid receptors and prevent withdrawal symptoms (Gynecologists 2017). Methadone is a full opioid agonist with a long half-life that is dispensed on a daily basis through a treatment program (Gynecologists 2017; Stanhope, Gill, and Rose 2013; Meyer and Phillips 2015). Unlike methadone, buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist that makes overdose less likely, allowing it to be prescribed and administered at home (Gynecologists 2017; Krans and Patrick 2016; Haycraft 2018; Stanhope, Gill, and Rose 2013; Meyer and Phillips 2015).

Treatment of OUD in pregnancy can employ these opioid agonists and is geared towards a multi-disciplinary approach to include appropriate pregnancy care and fetal monitoring to decrease risk of pregnancy morbidities (Gynecologists 2017; Haycraft 2018; Stanhope, Gill, and Rose 2013). Pregnant patients with OUD that do not seek medical assistance, have been shown to have decreased or lack of prenatal care; and increased risk of fetal growth restriction, placental abruption, fetal demise, preterm labor, neonatal abstinence syndrome, and meconium at the time of rupture of membranes (Gynecologists 2017; Stanhope, Gill, and Rose 2013).

Neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) is a drug withdrawal syndrome seen in 30-80% of pregnancies complicated by OUD, antidepressants, or opioid agonist therapies (Gynecologists 2017). With the increased used of opioids, the incidence of NAS increased from 1.5 to 6.0 cases per 1,000 hospital births from 1999 to 2013; representing a cost of $1.5 billion (Gynecologists 2017). Neonates experience gastrointestinal and nervous system disturbances within 12 hours to 14 days of life; leading to irritability, high-pitched cry, and poor sleep (Gynecologists 2017). Studies have shown that symptoms do not depend on maternal dosage of methadone; but can vary with split methadone dosing or with the use of buprenorphine (Stover 2015). Breastfeeding has also been associated decreased severity of NAS symptoms, less need for pharmacotherapy, and a shorter hospital stays (Gynecologists 2017).

Although the severity of NAS symptoms has not yet been shown to be affected by maternal mental disease, studies have shown a positive correlation between maternal mental health disorders and the incidence of NAS (Pediatric Academic Societies 2018). Faherty et al, demonstrated a 26% prevalence of depression in mothers of infants with NAS compared to infants of mothers without any mood disorder (Faherty et al. 2018). Mothers with OUD and infants with NAS also had double the risk of depression compared to controls; as well as, 2.2 times the risk of bipolar disorder, and 4.6 times the risk of schizophrenia (Faherty et al. 2018). Other studies have also showed that mothers of infants with NAS had higher chance of suffering from anxiety and postpartum depression, with rates of 27% and 7% respectively, compared to mothers of infants without NAS (Pediatric Academic Societies 2018).

In addition to these pregnancy complications, women with OUD are also at increased risk of abusing non-opioid drugs and psychiatric disorders (Gynecologists 2017; Holbrook and Kaltenbach 2012). Watkins et al found that approximately fifty percent of non-pregnant patients entering a substance abuse program screened positive for a co-occurring psychiatric illness with depression and anxiety being the most common (Watkins 2004). In those treated with methadone with either a mood disorder or anxiety disorder, patients were more likely to have a positive urine drug screen (UDS) and less chances of success with attempts of treatment for OUD in pregnancy (Fitzsimons 2007).

The purpose of this study is to compare the differences in buprenorphine doses needed to treat opioid use disorder in pregnant women with and without mood disorders; and to compare the development of neonatal abstinence syndrome in infants delivered to mothers treated with buprenorphine in patients with history of mood disorders versus those without mood disorder.

Methods

This a retrospective cohort study of pregnant women treated with buprenorphine for OUD through an outpatient OUD program initiated in March 2015 at Indiana University under the division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. IRB approval was obtained for this study. Women were included in the study if they had at least one outpatient visit with our center during pregnancy during which they were prescribed buprenorphine and delivered within the Indiana University Health system. Exclusion criteria included patients that: 1) delivered outside of our hospital system and delivery information was unavailable; 2) had a miscarriage or fetal demise; 3) were undelivered by time of data collection; or 4) were non-compliant with an outpatient visit. After obtaining IRB approval, electronic health records were reviewed for maternal demographics, maternal medical history and prescription use, including dose at initiation and delivery, and delivery data. Upon initiation of buprenorphine, patients’ social and medical history was recorded including history of current and prior illicit drug use, history of psychiatric disorder, prior psychiatric treatments or hospitalizations, and family history of psychiatric illness and drug use.

Analyses were performed to determine if there was a significant association between the maximum buprenorphine dose used in our clinic (24mg) and outcomes of interest. Maximum dose was determined by taking the maximum out of the four dosing times or periods (first, second, and third trimester and delivery). Student’s t-tests and Analysis of Variance models were performed when comparing dose across levels of categorical variables for two and more than two levels, respectively. Chi-Square tests were used when testing for homogeneity between levels of categorical variables. Correlation analyses were performed when comparing continuous variables to dose. All analytic assumptions were verified. When data were skewed, non-parametric tests were performed, as data transformations were unable to correct the skewness, with Wilcoxon-Kruskal-Wallis rank-sum and Spearman correlation analyses being performed. Fisher’s Exact tests were used to verify the results of Chi-Square tests when expected cell counts were small. All analyses were performed using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Four-hundred and nine pregnancies were treated through our clinic from March 2015 to December 2018. One-hundred and forty-three were excluded due to one of the exclusion criteria. Of the remaining 266 pregnancies, 171 were noted to have either a history of mood disorder or were actively receiving medical treatment for mood disorders. The three mood disorders reviewed included depression (n=148), anxiety (n=130) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD, n=19). Over forty percent of the patients had diagnosis of more than one mood disorder.

There was no significance differences in maternal age, marital status, education level, or parity of subjects with or without a mood disorder (Table 1). The average age of first drug use was approximately 20 years old with no difference between the groups. While the first substance used was more likely to be opioid pills in both groups (51.6% with no mood disorders vs. 49.4% with); those without a mood disorder were more likely to have used heroin and those with mood disorder were more likely to have used benzodiazepines (p=0.0046). There was no difference in tobacco use among the groups.

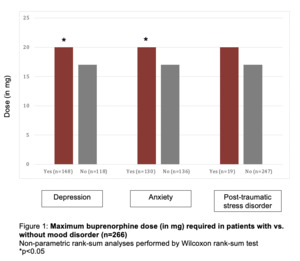

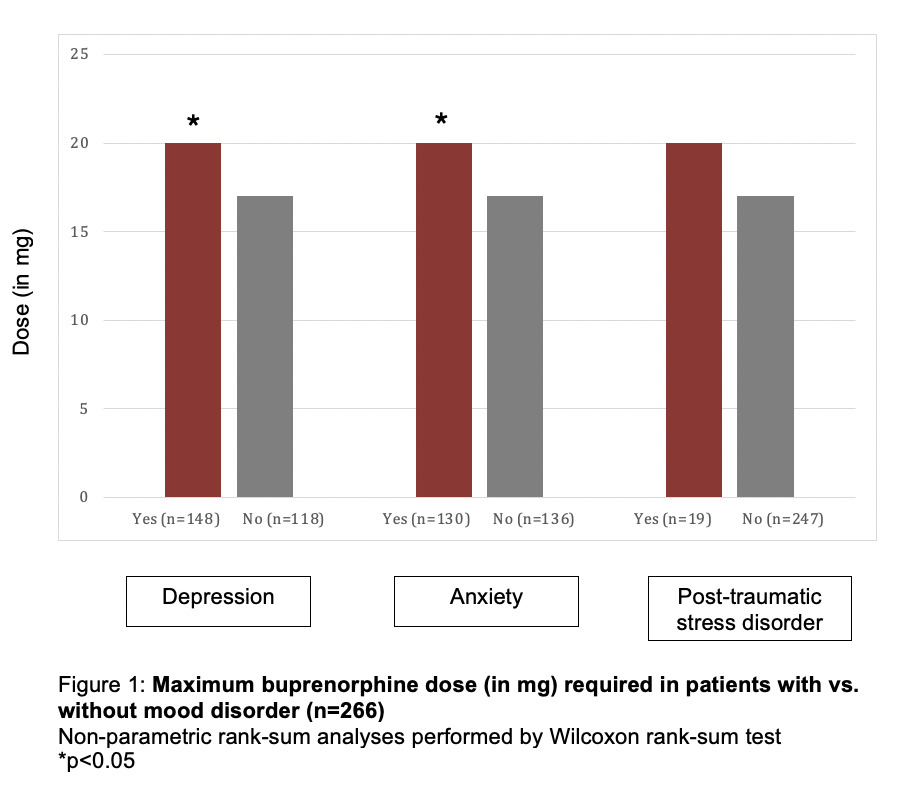

Both groups initiated treatment of OUD with buprenorphine in pregnancy during the mid-second trimester, but patients with mood disorder were more likely to have had prior treatment attempts in the past (74.7% vs. 62.0%; p=0.0453). When compared to patients without mood disorders, those with depression or anxiety required a significantly higher maximum dose of buprenorphine (median doses for both disorders 16mg vs. 20mg; p=0.2017 and p=0.0165, respectively). Maximum dose of buprenorphine used in our clinic for treatment of OUD in pregnancy is 24mg, at which point patients are offered treatment with methadone instead buprenorphine for further management of OUD. There was no significant difference in the doses of buprenorphine for those with PTSD alone (Figure 1).

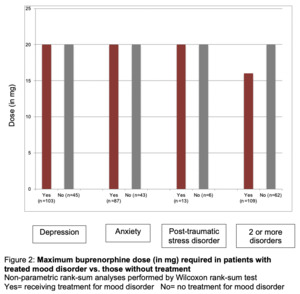

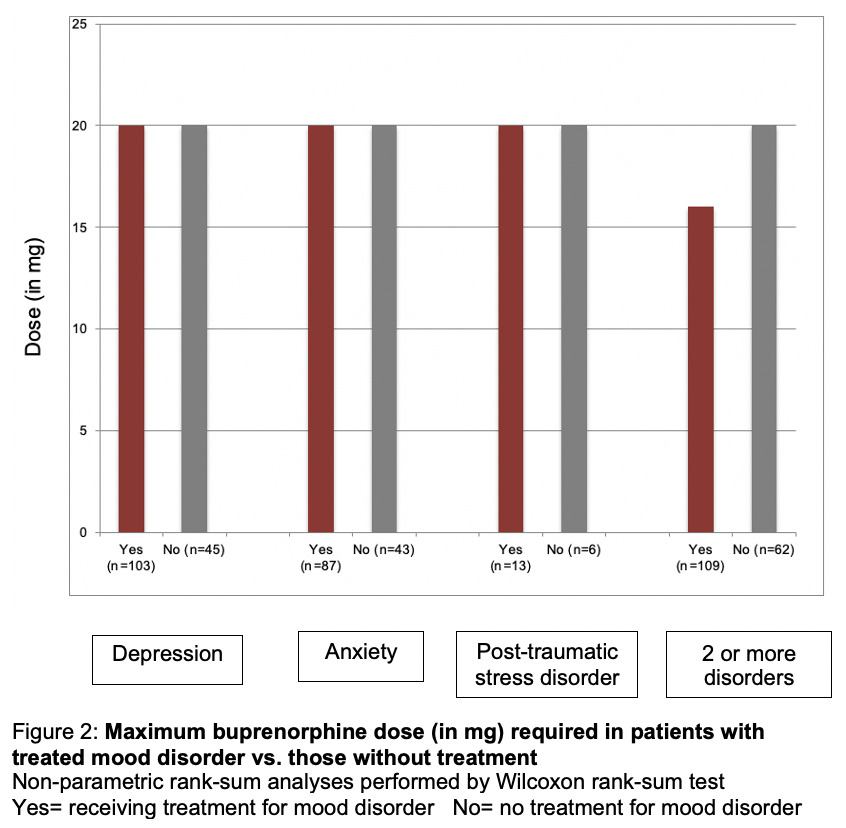

The dose of buprenorphine was then compared to those patients with mood disorder receiving active medication treatment of their mood disorder versus those not receiving treatment. Patients treated for depression, anxiety, or PTSD had no difference in their maximum required dose of buprenorphine compared to those not actively prescribed medication. There was also no difference in buprenorphine dose those with multiple mood disorders (Figure 2).

Results also showed that there was no difference in the development of NAS in infants of mothers with and without mood disorders (Table 2). In cases of depression, the difference of NAS was 56.5% vs 43.5% (p=0.65); meanwhile for anxiety, it was 52.2% vs 47.8% (p=0.22), and 6.5% vs 93.5% for PTSD (p=0.744). Even for cases of combined mood disorders, there was no difference in the incidence of NAS with 66.7% vs 33.3% (p=0.3053). These differences in the incidence of NAS were not affected by the use of psychiatric treatment (depression p=0.66; anxiety p=0.50 PTSD p=0.59, Table 4).

If NAS did develop, the length of hospital stay varied depending on the mood disorder (Table 3). Infants of mothers with anxiety and PTSD had a longer duration of NAS related symptoms, 6-51 vs 2-42 days (p=0.0088) and 10-25 vs 2-52 days (p=0.0291) respectively; compared with combined disorders and depression which had a NAS symptoms duration of 2-51 days (p=0.38 and 0.16 respectively). No difference in length of stay was seen in infants of mothers being treated for their mood disorders (Table 5). There were also no statistically significant differences between birth weight and incidence of NAS when comparing races. There was also no difference in NAS development in breastfed infants among those patients with mood disorders.

Discussion

While the safety and efficacy of buprenorphine for the treatment of OUD in pregnancy has been well established, there is little information available on the effect of underlying mood disorders on treatment dosage. Prior studies in both pregnant and non-pregnant patients have noted that a portion of these patients have additional underlying psychiatric disease that may impact treatment success. However, there are no prior studies to our knowledge that have evaluated buprenorphine dose requirements in pregnant women with OUD and mood disorders.

Our results showed that more than half of our patients treated with buprenorphine for OUD also have a diagnosed mood disorder; with up to 40% having 2 or more mood disorders. This correlates with findings of the general population which show approximately 32% of patients have concurrent opioid use and mood disorders (Quello 2005). In our population, mood disorder diagnosis did not significantly vary by age, marital status, education level, or parity of women. The existence of a mood disorder did influence dosage requirements, as patients with depression or anxiety required a higher maximum dose of buprenorphine. The increase of buprenorphine dosage in pregnancy without accounting for mood disorders is well known. Caritis et al concluded that pregnant patients required more frequent dosing intervals to sustain plasma concentrations of buprenorphine of more than1 ng/mL to prevent withdrawal symptoms and improve adherence (Caritis et al. 2017). However, knowing that there is an additional possible increase in dosing needed with mood disorders based on this study, can potentially help guide the pre-pregnancy and pregnancy counseling of these women.

The results also provide data to develop better plans of care for patients during their pregnancy; and discuss realistic pregnancy and postpartum expectations with patients. For example, although there was no increased risk of NAS development in infants of mothers with mood disorders, there was an increased length of hospital stay for infants of mothers being treated for anxiety and PTSD. Therefore, the prenatal care of these patients should include discussion of possible neonatal expectations and side effects after delivery.

One of the strengths of this study is that our treatment group in pregnancy represents a large group of patients on buprenorphine in a single center. We believe that having an active treatment center for patients with OUD in pregnancy allows for improvements in pregnancy care through a single office compared to patients requiring treatment by both an OUD center and obstetrics.

However, the study is limited by its retrospective nature. We were limited by information available in the medical records over a 3-year period. Some of the patients were included based on a self-reported history of psychiatric illnesses and not confirmed via prior validated testing in patients not on current medication for their mood disorder. In addition, some of the sample sizes for certain mood disorders, like PTSD, were small.

Conclusions

The risk of NAS in mothers with OUD has been studied extensively but there is limited data on how mood disorders affect the risk of NAS in this population. This study provides data that can help guide the providers for proper counseling of these women in discussion of their pregnancy and post-delivery expectations. Results from this study show that a difference in dosage exists, and that patients with mood disorders may require higher dosing than those without these disorders. While additional studies are needed to review the best treatment practices for combined OUD and mood disorders, this study offers baseline knowledge for development of these treatment modalities. Further studies continue through our program with the assistance of psychiatric and counseling services to improve care and pregnancy outcomes for this patient population.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the ancillary staff of the Indiana University School of Medicine Maternal Fetal Medicine office who assisted in collecting patient lists from the time of initiation of this program for medical record review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Funding

No funding used for the completion of this study.

Presentation

Presented at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Annual Clinical and Scientific Meeting; Nashville, TN; May 3-6, 2019; additional data presented at the Central Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 86th Annual Meeting; Cancun, Mexico; October 16-19, 2019

Corresponding Author

Tiffany Tonismae, MD

Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital

Maternal, Fetal, & Neonatal Institute

600 5th Street South, 5th Floor

St. Petersburg, FL 33701

(c) 803-530-0493